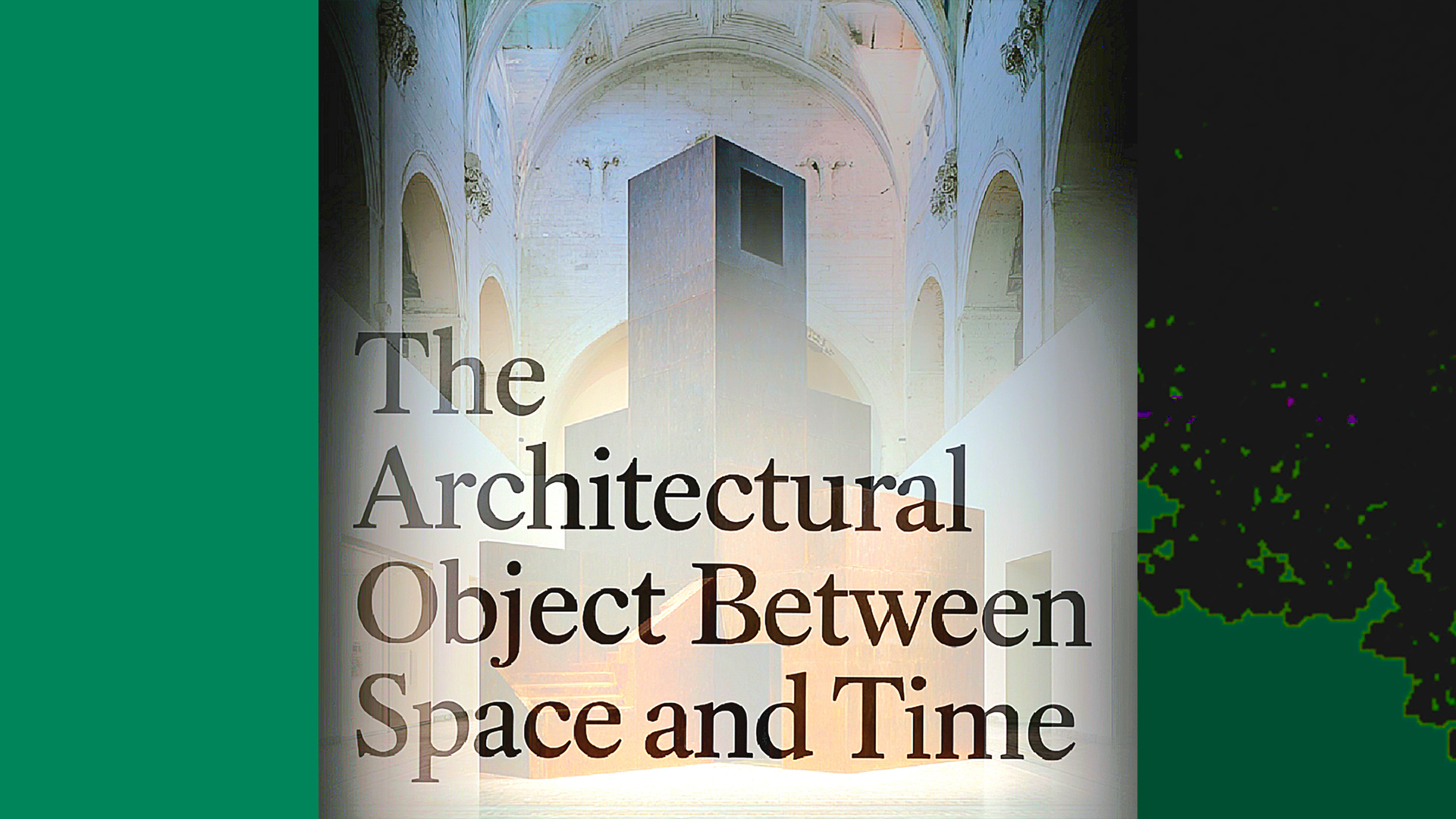

Design of New Words

The Architectural Object Between Space and Time

- Design of New Words

- The Architectural Object Between Space and Time

The Architectural Object Between Space and Time

Analyzing the architectural object

within the framework of the two principal currents of thought allows us to delineate the temporal thicknesses of architectural matter. At first glance, it is essential to emphasize the absolute priority of the formal argumentation that developed in relation to the theme of abstraction; in both cases, the architectural object remains a physically determined construct, defined by its spatial coordinates. Yet the expanded vision introduced by Einstein’s theory of relativity adds the temporal parameter to these “classical” coordinates.

The qualitative shift, in fact, does not produce substantial modifications in the conceptualization of the architectural project, but it intervenes formally within the decompositional language of Neoplasticism, understood as a linguistic model that enacts a true and proper destruction of the object.

In the subsequent formal recomposition of the work, only a few strokes are added to the object’s ideal morphology. The outcome, methodologically coherent, nonetheless bears the mark of the interchangeability of its individual parts. Its apex, reached through the interplay of multiple syntaxes, unfolds through often intuitive commutations, oscillating among absolutes still only partially perceived and far removed from the singularity that distinguishes the occasional work from the strictly architectural one.

The house appears as a construction of separate fragments which, though nominally belonging to a unified whole, continue to exalt the decompositional model of superposition and separation between structural elements and color.

The presumed rhythmicity of neoplastic works alludes to a conception of time applied to space, yet it remains firmly anchored in the abstract vision of the “revealed” elements: vertical and horizontal lines, primary colors. In this context, the notion of architectural metrics requires further specification, particularly in relation to the musical discoveries that introduced composite metrics, those structural innovations that shaped the avant‑garde of sound.

One could elaborate at length on the ambiguities that structure sensory experience, yet architecture’s incapacity to accommodate supersensory or trans‑phenomenal visions produces an intrinsic condition of stasis, even at the level of its ostensibly speculative formulations. Futurism, together with the Futurists’ programmatic attempt to dismantle the grammatical codes of composition, ultimately performs little more than a critical exegesis of linguistic and perceptual conventions. It does not, however, achieve the transformative outcomes previously theorized or codified within its own avant‑garde discourse.

The anticipated rupture from commonly shared sensory paradigms fails to occur even within the conceptual domain. Although contemporary artistic practices increasingly acknowledge the expansion and destabilization of spatio‑temporal categories, they nevertheless reveal an unresolved tension: art has yet to fully internalize, let alone transcend, the Cartesian framework that continues to underwrite its epistemic and perceptual assumptions.

Countless attempts have been made to attribute a scientific character to architecture; the obsessive interest in science applied in the architectural field, partly produced by organic cataloguers, promotes a poetics of intervention accustomed to numerical poetics, still distantly perceived in purely spatio‑temporal terms.

The language transplanted from the obscure and polemical theoretical veins revived in the 1970s does nothing but announce the eventual defeat of an architecture stretched toward the enumeration of terms, methods, and three‑dimensional schemes, conveniently translated into anti‑perspectival four‑dimensionality.

Assiduous supporters of architectural “freedom,” discovered through formulas of negation, preserve an unaltered field of cognitive inquiry, believing they can annihilate creative processes assimilated from the multiple visions of being. After all, even the results still observable today suffer from the absolute lack of interaction between analytical methods and the works produced.

The freedom glimpsed in Le Corbusier’s plans, taken as a benchmark for contemporary architecture, introduces a disquieting value of uncertainty, abstraction, and incomprehension, positioning itself as a mere antithesis to the classical world. Even the cosmos of abstraction renounces the appearances of nature, yet it has never excluded the axis that connects to the interior of form, dictated by the universality of the absolute.

Ridiculous anti‑classicisms reveal once again, in history, the impossibility of creating from nothing and the persistent need to draw, even in linguistic definitions, from the invariant spatial concept derived from the Classical, understood not as the sum of events preceding the Modern, but as a stellar point of reference within a universe in continuous mutation. After all, as Klee observed, even in art there is ample room for exact research.

Whether humanity appears to distance itself from the aesthetic dimension of nature through abstraction, or to assimilate its forms in a naturalistic manner, is of limited significance from a compositional perspective, and even less so in relation to techniques of invention. What truly matters is the pursuit of understanding phenomena, whether they unfold outside the individual or within the depths of the psyche. In this sense, art becomes a vital instrument of inquiry, for it contains within itself multiple pathways through which human knowledge can develop.

Architecture, perhaps more than any other discipline, and precisely because it draws upon languages from multiple generative sources, must be understood as the expression of a continuous process of inquiry. It is the practice through which space is transformed to accommodate the physical and psychic needs through which human beings articulate their presence in the world. It is through intuition that we reach knowledge, moving beyond the limits of concepts and scientific laws, and perceiving the becoming of reality itself.

Art already contains a form of intuition, as Bergson suggests, an intuitive power capable of entering into the interior of things more deeply than any scientific description. From this perspective, art acquires a value that can even surpass that of science, precisely because of this unique capacity for penetration and insight.

Recognizing that our being rests on a bipolar tension between intelligence and instinct, inseparable and mutually sustaining, expands the evolutionary potential of the human creature. Intelligence carries the mark of artificiality, while instinct is granted the natural capacity for immediate immersion in reality. Yet when instinct rises to a heightened level of awareness, it ceases to be mere instinct and becomes intuition.

These reflections can be placed alongside those of Charles Tart in PSI: Scientific Studies of the Psychic Realm. Rather than relying on philosophical speculation, Tart turns to the statistical analysis of controlled laboratory experiments. In his work, he discusses the mechanism of lateral inhibition, a process that sharpens our focus on the immediate present while acknowledging the mind’s inherent capacity to probe both past and future. From this emerges the hypothesis that one can deliberately “defocus” the present in order to become aware of the future, anticipating the needs of the individual as well as those of the broader social system. Although expressed in a different linguistic register, such behavioral models, if interpreted with care, may offer unexpected cues for developing new techniques of architectural intervention.

One might therefore infer that the senses serve less to admit information into the psyche than to keep it out, allowing the nervous system to operate as a protective filter against the intrusion of “precognitive” material. From this perspective, forgotten systems of wisdom do not disappear; they re‑enter experience through alternative channels of reception embedded within traditional language. Among these channels, art remains one of the most potent.

The absolute Self, understood as the widest horizon of consciousness, if freed from the constraints and inhibitions imposed by the “organizing filter” of the partial self, could access an immense range of information originating from sources unknowable to ordinary perception. In this view, a painting, a piece of music, or an architectural form become verification diagrams for the sensitive qualities of the higher self: a true laboratory for observing the becoming of inner and absolute reality.

The search for the forms of the absolute has spanned millennia. It is not only with the recent investigations of abstraction that one finds attempts to establish an exchange between a higher Self and a partial self. From the earliest forms of writing, those to which modern thinkers repeatedly return, it is already possible to discern the effort to create a dialogue between what, on the external plane, is named as nature, and what, on the mental plane, within the sphere of human instinct, cannot be named at all.

Kandinsky’s Concerning the Spiritual in Art (1910), together with Klee’s writings, establishes the very syntax of abstraction—offering later generations not only the linguistic instruments of a new artistic communication, but also a calibrated equilibrium between the reality of existing and the reality of being, two primordial and indispensable dimensions of human definition.

From "Desin of New Words"

The Architectural Object Between Space and Time

by Filippo Lo Presti 1989