The Nature of Ornament

What for Michael Graves is a mimetic ornament, in Aldo Rossi becomes a conceptual ornament.

Even within contemporary architecture, the two values can be clearly distinguished: in Graves, the planimetric vision projects an architectural ornament most evident when perceived from above, as if one could imagine a script legible from the sky; in Rossi, by contrast, the “planimetric” conceptual ornament emphasizes the rational classicism of the sign.

Ornament, through the use of material, even in ephemeral contexts, proposes a scientific understanding of that material. It defines the juxtaposition of materials and their spatial limits within clear boundaries.

In the work of Aldo Rossi, the ornament of an opening (like a window) is simply its trace on the wall. Its identity as a window is conveyed not by a traditional arch or pediment, but by its essential, point-like presence. This act of certifying the window's existence in the real world negates the need for additional material juxtapositions of ornament. Thus, the architecture is adorned by its own essential elements.

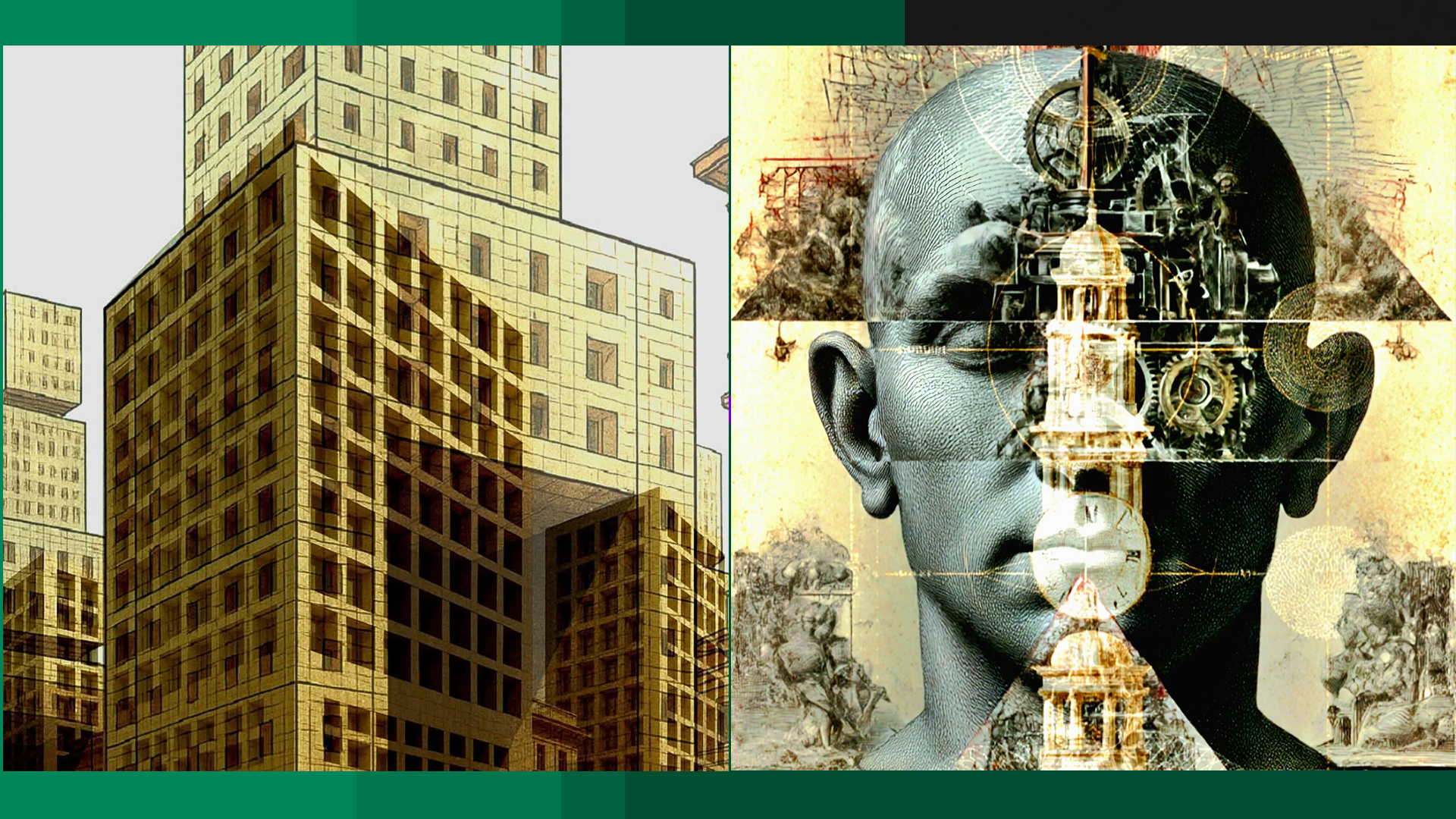

The decomposition of the world’s square grid, in relation to urban-scale theories, is one of the central themes in Leon Krier’s poetics. In this case, architectural ornament continues to operate at the scale of the city, as in the design of new neighborhood centers: it becomes a congestion between Mondrian’s equilibria and the syntaxes of the straight line rotated diagonally.

The megablocks, themselves composed of microblocks, emerge from the idea of the covered square to become, typologically, urban units. They are theatrical boxes, opening onto the streets of the historic center, recalling the modern while signaling their existence as new structures, forms of a generation steeped in the classical.

From brief allusions to this contemporary vision, we must return to the conception of ornament within the climate of the avant-garde, a period in which many certainties were deliberately unsettled, so that the “modern” could be assimilated into the architectural language of form.

The triad of Nature, Man, and Machine frames questions inherited from the Morrisian culture of ornament. The relationship and reciprocal exchange between machine and man would later be crystallized by the avant-garde, which, anticipating total destruction, proposed the erasure of rules in opposition to the ceaseless expansion of form.

The ornament, which may unfold over time in both mimetic and dynamic form, reveals with clarity the compositional pathways inherent in its origin. Mimesis in nature and mimesis in the dynamism of the act define the ornament within two renowned antithetical classes. Architectural ornament then emerges as the third element of the triad, synthesizing these two linguistic boundaries into the unity of the architectural work.

In architecture, disguise often begins as simple cladding, a surface treatment reminiscent of William Morris’s wallpapers. A more sophisticated form is makeup, which moves beyond decoration to conceal the load-bearing structure, embedding it within the building’s body and overlaying an autonomous façade.

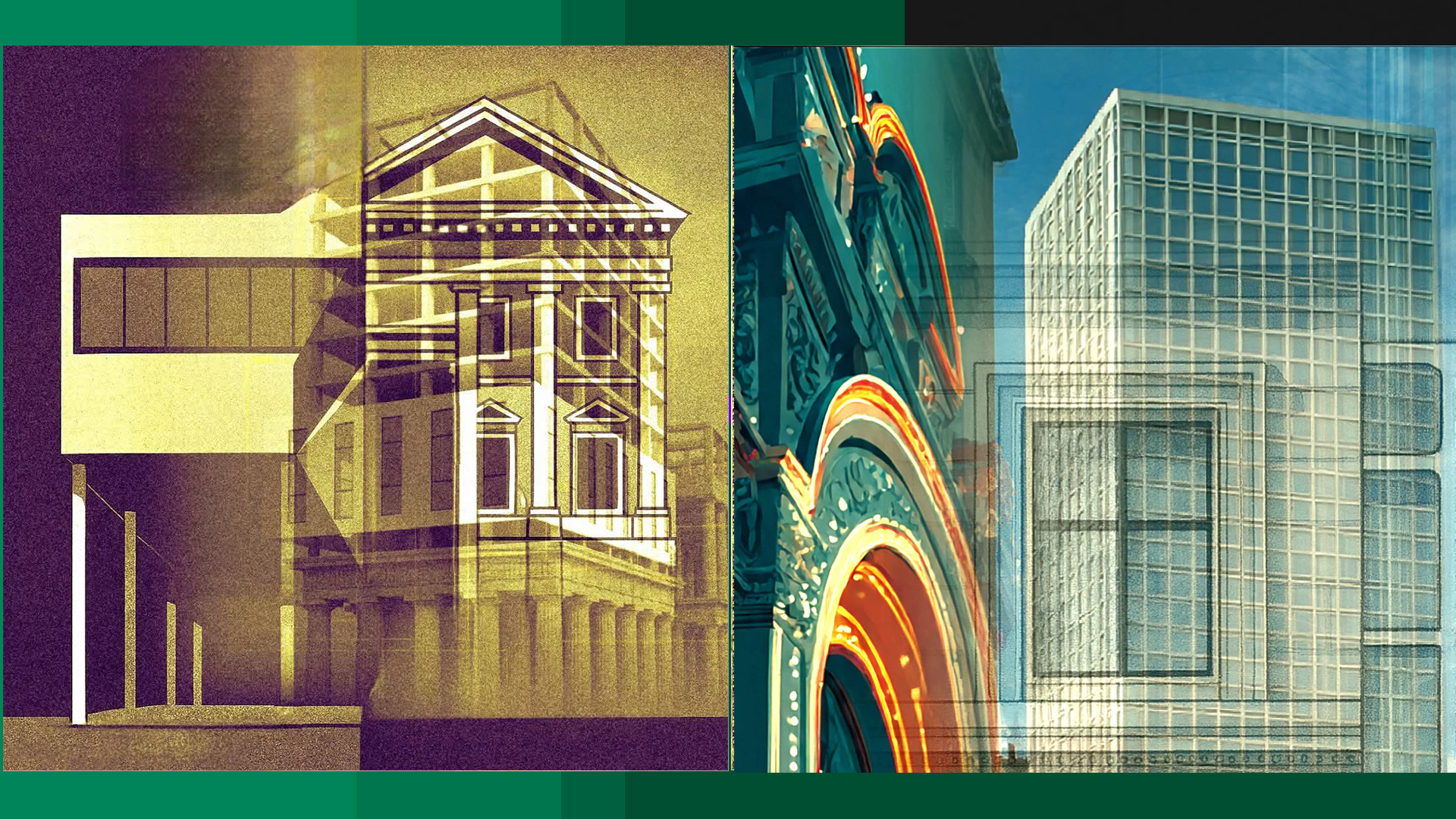

Le Corbusier’s notion of the free façade exemplifies this strategy, using a skin that deceives our perception of the building’s true form. Likewise, the optical and perspectival illusions of many classical buildings foster the temptation of perfect symmetry, an artificial construct achieved through visual tricks, all in the pursuit of eurhythmia, or harmonious proportion.

The deliberate, theatrical spectacle of Las Vegas architecture is fundamentally different from the modern, camouflaged ornamentation found in Europe. European mimetic architecture uses illusion in a rational way, creating a language that shapes our perception and understanding of a building. It's a mistake to equate Le Corbusier's innovative approach to the building façade with the unrestrained use of the American curtain wall. While these two architectural traditions sometimes influence each other, their core philosophies and ultimate goals often lead them in completely separate directions.

Standardization of building components should not be equated with the use of brick in classical architecture. In both cases a model is reproduced serially, yet in classical practice the placement of elements is conceived as both ornamental and structural. Modern assemblage, by contrast, does not so much compose architecture as it aggregates structural elements, thereby converting the assembled system into a model for living .

From "Design of New Words"

The Nature of Ornament by Filippo Lo Presti 1989